Portrait of Giuliano de Medici by Raphael

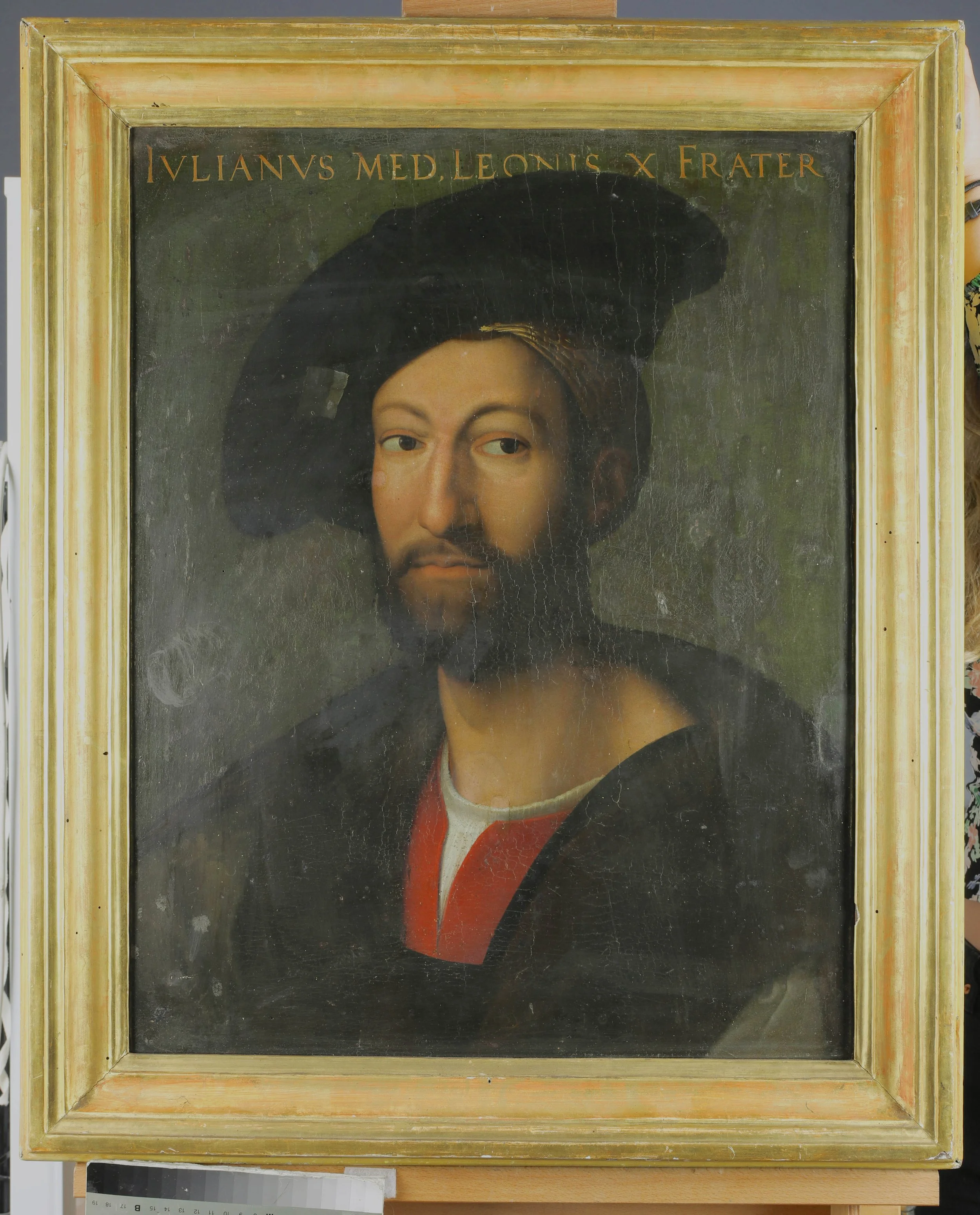

The picture before treatment

After treatment, and framed in a period-appropriate frame

Our client brought this painting to our studio in 2019 having recently purchased it at auction in Italy as a work of the Florentine School. He had a hunch it might be Raphael’s original portrait of Giuliano de Medici, of which various versions are known including an early copy at the Metropolitan Museum in New York.

Our senior conservator Majo Prieto Pedregal assessed the painting and agreed a treatment plan with the owner, as well as recommending various avenues of scientific analysis to find out more about the portrait.

The results have been nothing short of fascinating.

The removal of at least two layers of aged varnish and extensive old retouching has transformed the painting, revealing Raphael’s delicate brushwork beneath, which had remained in remarkably good condition through the centuries.

One of the biggest surprises? Tiny hairs on Giuliano’s shoulder! Majo’s cleaning uncovered Raphael’s original intricate depiction of individual hairs.

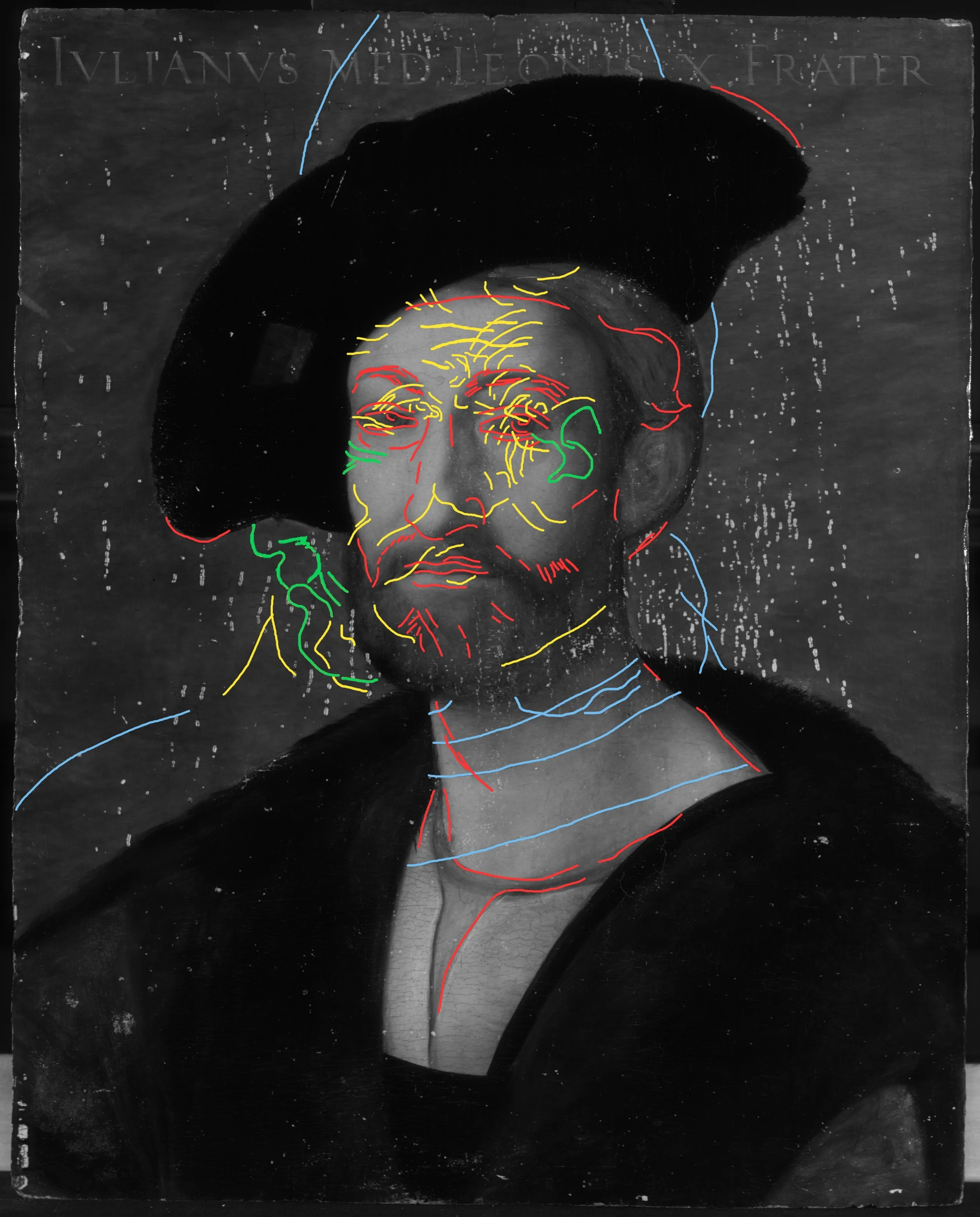

Infrared imaging also exposed numerous underdrawings, including a fascinating frontal portrait beneath the surface, offering insight into Raphael’s creative process.

A detail of the seal on the reverse of the panel

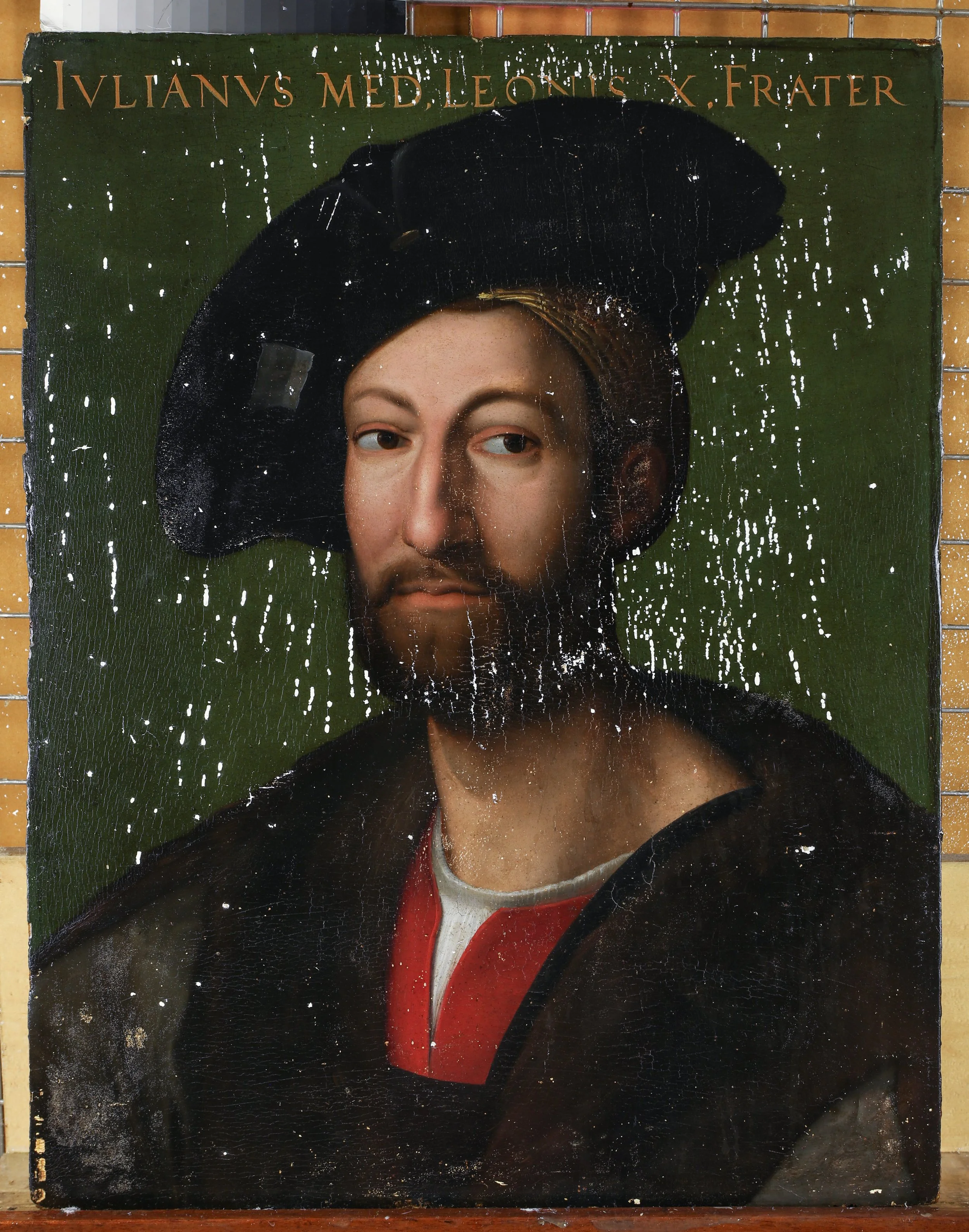

The portrait after cleaning (which involved removal of at least two old layers of varnish as well as old retouching) and filling, ready for retouching to begin. We were delighted by the overall excellent condition of the original paint layer, with only small losses sustained in the painting’s long history.

A detail of the edges of the panel where gesso drips are visible, indicating that the panel has not been cut down since the artist prepared it for painting.

The painting after precise retouching.

After treatment, in 2020 the painting was seen by Professor Tom Henry, who wrote: “There are a number of portraits of Giuliano de' Medici (1479-1516), Pope Leo X's younger brother and Duke of Nemours, but no unanimity exists regarding which of these is Raphael's original. That such a picture existed is clear from letters written within a year of the picture being painted (further discussed below), and after the sitter's death Raphael's painting spawned numerous copies, including Vasari's fresco in the Palazzo Vecchio (which was based on knowledge of Raphael's original then in the possession of Ottaviano de' Medici in Florence), and a panel attributed to Alessandro Allori in the Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence (inv. 1890, n. 775). One version, rediscovered in the nineteenth century in Florence and now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (inv. 49.7.12, Img X), was widely accepted as a work by Raphael in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries but was increasingly dismissed as a copy or as a workshop replica of a lost original. The version in New York is painted on a fine canvas, and does not appear to be a transfer from a wooden support. It has suffered very extensive abrasion throughout, and there are large areas of retouching. Further comment on its compromised condition is offered by the current author in his entry on the New York picture when it was displayed in Madrid and Paris in 2012-13 (as Raphael and Workshop).It remains to be clarified what the original looked like. The version in New York is, in fact, an outlier amongst the various versions. It shows the sitter's hands resting on a table, the top of the figure's left arm and a view beyond of the Castel Sant'Angelo and the ramparts (the Passetto) that link this building to the Vatican palace. I am only aware of one, weak, copy after this composition in its entirety, i.e. also including the Castel Sant'Angelo and a section of the Borgo Alexandrina. A second group of pictures again show the seated figure half-length, holding a letter, and it was this model that Allori followed in his later sixteenth-century copy. Notably these half-length versions all frame the figure as in the New York version. A final group only shows the head and shoulders of the sitter, always against a green curtain. The most likely scenario is that this final group is a reduced version of the larger prototype, but one cannot be sure that this was the case; and de Maffei (1959) argued that the head and shoulders format was the original solution (when promoting a version, then in a private collection, as Raphael's original). Vasari's frescoed copy in the Palazzo Vecchio could have depended on any one of these compositions. Later in the century the composition was developed as a three-quarter length by Pieter de Witte (Pietro Candido) in another painting in the Uffizi.The early references to the picture do not help to resolve the issue. On 19 April 1516, one month after the de facto ruler of Florence Giuliano de' Medici had died, Pietro Bembo wrote to Cardinal Bibbiena and noted in passing that the portraits of the late Duke and of Baldassare Castiglione (probably a lost picture and not the portrait of Castiglione in the Louvre) 'parrebbono di mano d'uno de garzoni di Raphaello' in comparison to Raphael's portrait of Antonio Tebaldeo (also lost). This is clear evidence that Raphael, or his workshop, had painted a portrait of the Duke, perhaps to coincide with Giuliano's appointment as Captain-General of the Church in June 1515 or on the occasion of his marriage to Philiberte de Savoie in January 1515, at which time he was created duc de Nemours. That the sitter is shown with a beard apparently confirms a date in 1515 as a medal dated to this year shows that Giuliano grew a beard when he moved from Florence to Rome, where he was recorded between 31 March and 7 July 1515.During this period there is a reference in Giuliano's household accounts to one 'Raphael of Urbino' as a salaried retainer. It is quite possible that Raphael could have received a salary of this type from the Pope's brother (a position recently restated by Carmen Bambach in her discussion of Leonardo's position in Giuliano's retinue), but in the absence of any other corroborating evidence it should be acknowledged that this individual could be a different person.Raphael was one of the very greatest portrait painters of his age, and we know a good deal about his Roman portrait practice. As the letter referred to above suggests, and as corroborated by other correspondence, e.g. regarding the portrait of Isabel de Requesens in the Louvre, Raphael frequently relied on assistants when painting portraits. This was more commonly the case in formal, commissioned portraits and does not seem to have occurred with the (more intimate) portraits of his friends. His Roman portraiture comprises Cardinals and papal courtiers, as well as portraits of Popes Julius II and Leo X, formal portraits of members of the Medici family and of a Neapolitan beauty for King Francois Ier, as well as more intimate portraits of private citizens and friends (both male and female). The majority of these are at least half-length and include one or both of the sitter's hands.Turning to the current painting nothing in its technique undermines the conclusion that it is a work from the first half of the sixteenth century. The picture is painted on a single poplar plank, which has a vertical grain. There is no evidence that the picture has been cut down (gesso drips are visible on the edges), and yet it is painted right up to the edges all round. It is somewhat unusual not to find an unpainted area where a panel has not been cut. The choice of panel and its preparation are otherwise typical of the period. In this period Raphael painted portraits both on canvas and on wood, and very little can be concluded from the choice of support. Formal portraits of important sitters rather than friends are more often on panel, but even here there are exceptions.”

An infrared image with drawing lines of several other compositions marked up digitally in different colours to aid interpretation.

A detail showing the tiny hairs revealed on Giuliano’s shoulder

Detail of the infrared with drawing lines of one of the other portraits beneath the present composition.

The painting in the studio after treatment, with Simon Gillespie ACR, Majo Prieto Pedregal ACR, and Maria Giulia Caccia Dominioni ACR