A Magnificent Qajar Group Portrait

Attributable to ‘Abdallah Khan Naqqashbashi (active 1800-1850)

Iran, c. 1810-20

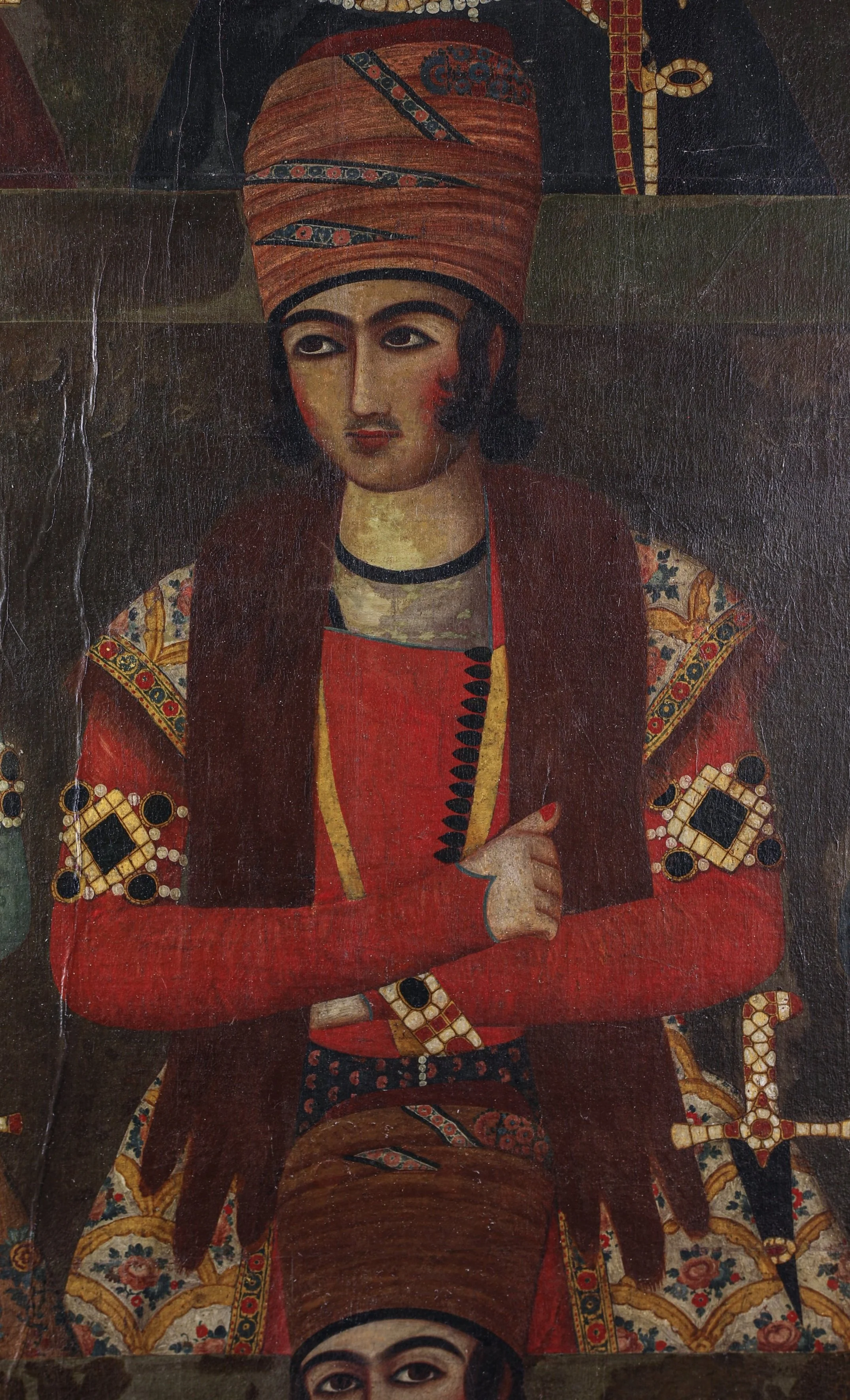

Before treatment

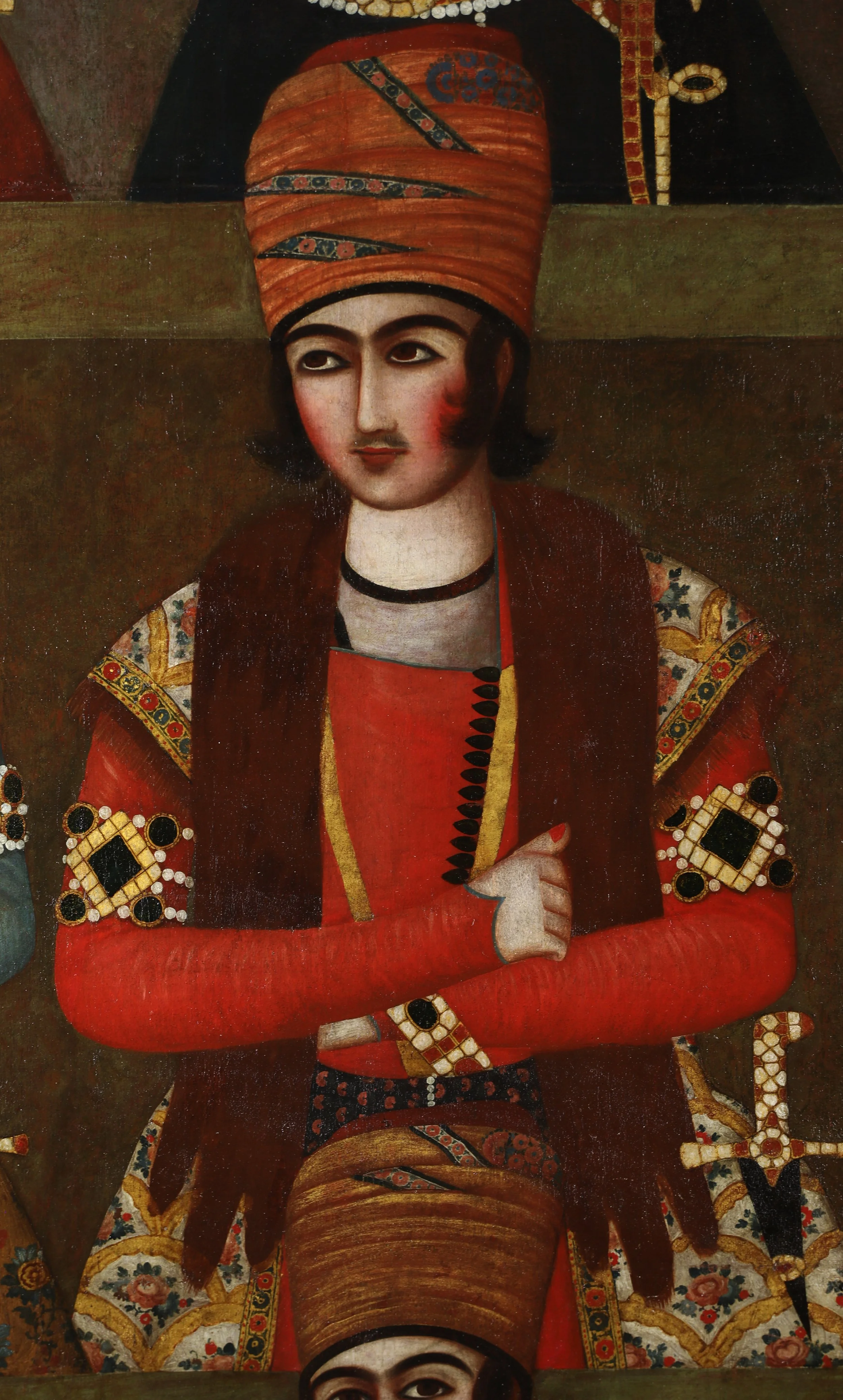

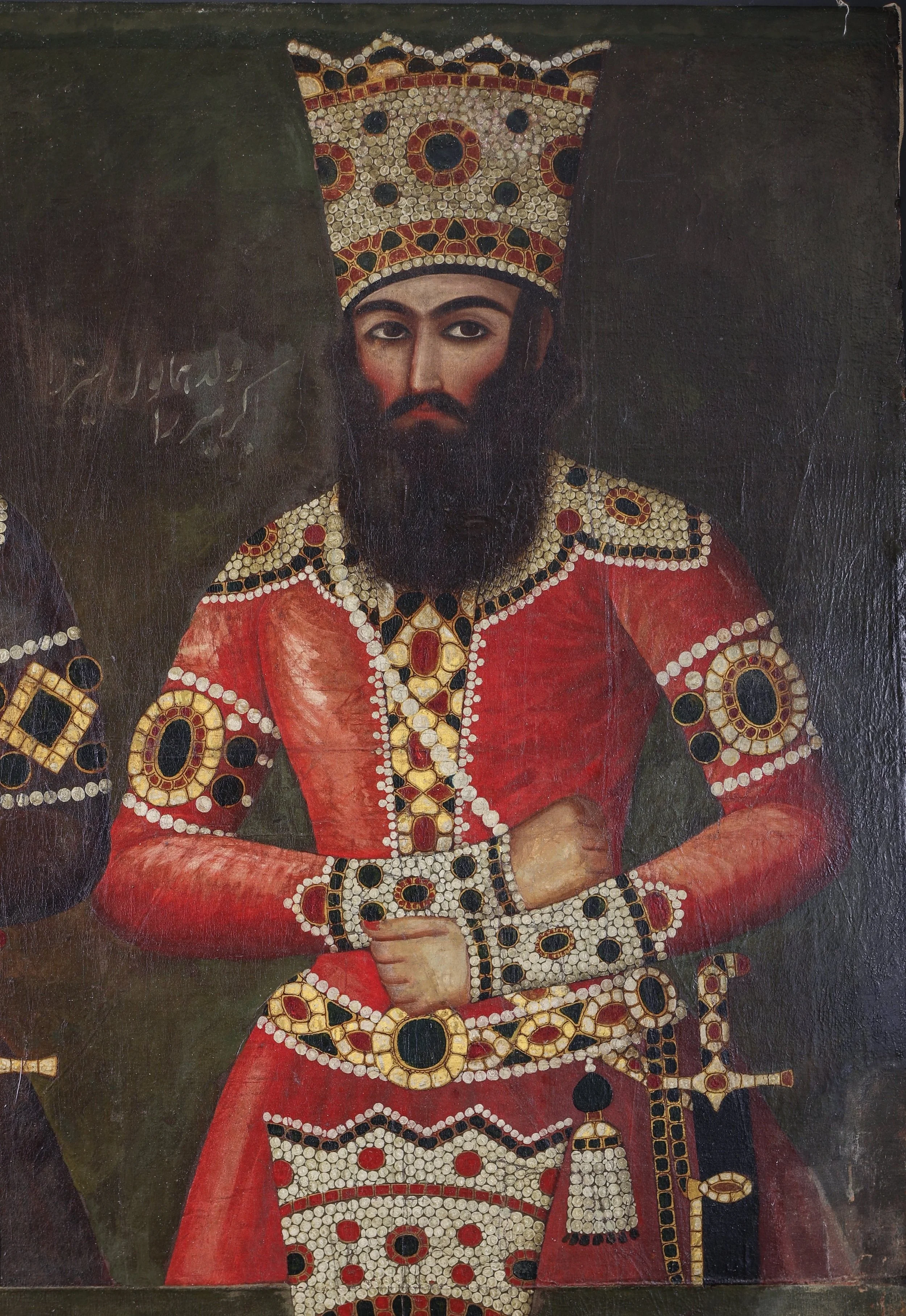

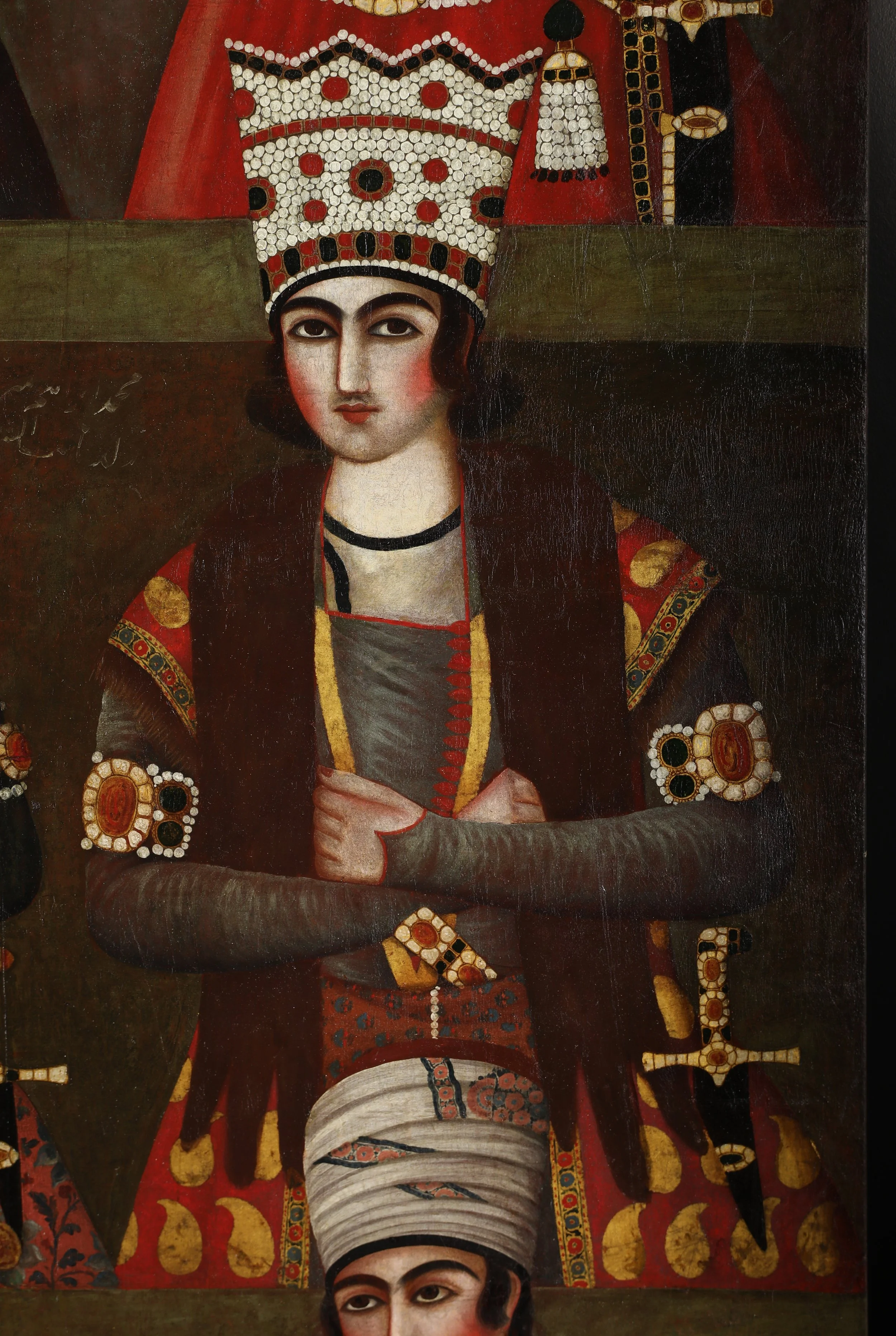

After treatment

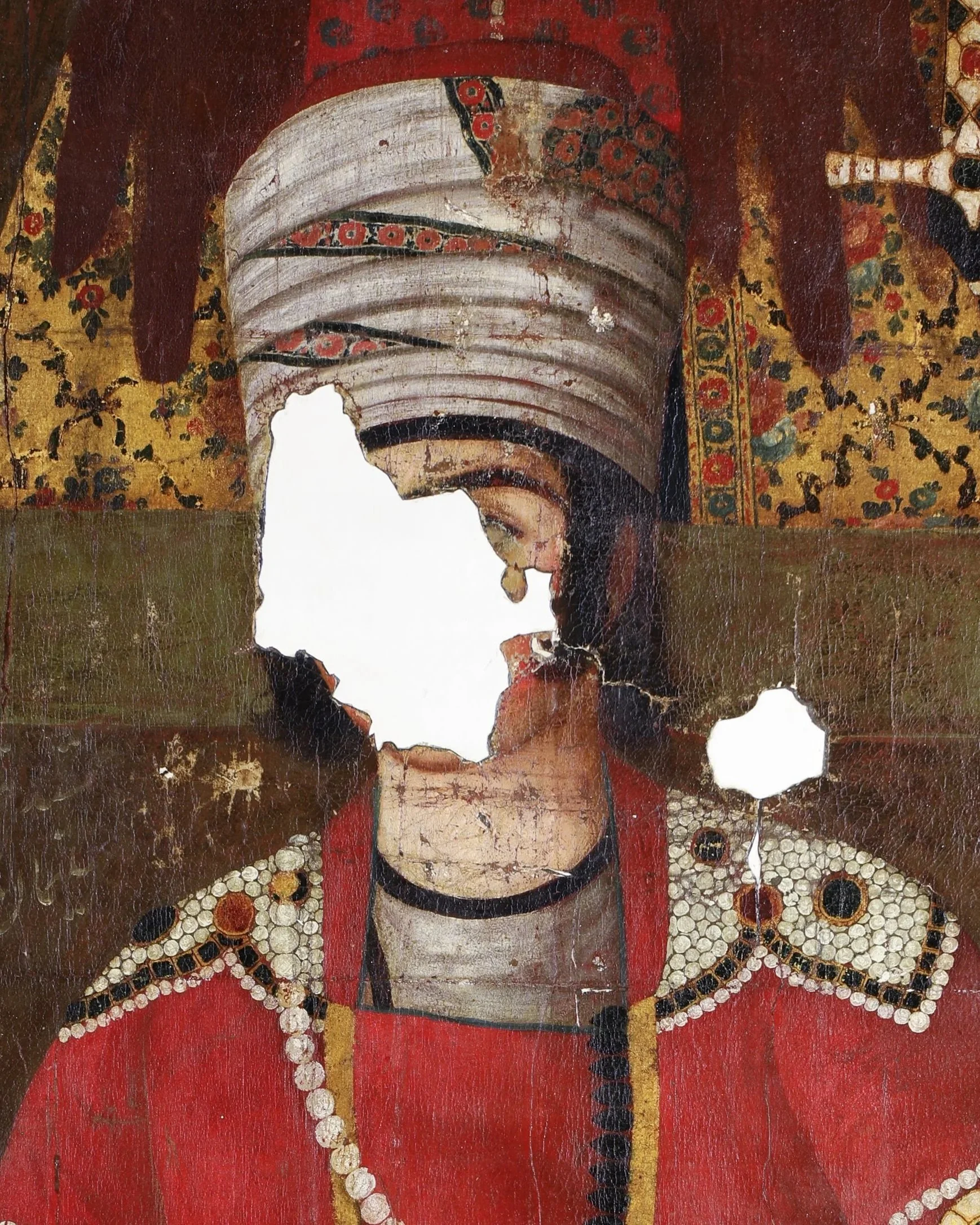

During treatment

This very large painting (255 x 440 cm) was one of the most memorable pictures we have treated, requiring the whole team at Simon Gillespie Studio to come together and contribute their expertise.

Painted with oil heightened with gold on a canvas support, the painting depicts twenty-four royal courtiers portrayed in three rows of eight, all standing facing left and wearing lavish robes and turbans or crowns, each figure is identified in Arabic script painted in white with an inscription giving the title and patrilineal or matrilineal descent of each prince. It is one component of what would originally have been a tripartite composition which once would have decorated the main hall of a royal Qajar palace of the second decade of the 19th century; the central canvas would have depicted Fath ‘Ali Shah seated on the Peacock throne with his eldest sons, and the panels to each side would show the Shah’s sons and grandsons: a total of about 100 figures. Commissioned by Fath `Ali Shah, this painting would have been completed by a team working under the supervision of the principal court artist, `Abdullah Khan. Fath`Ali Shah was the first shah to re-unite the country of Iran after seventy years of unrest. To mark this turning point in history, he created a new capital: Tehran. His reign is noted for its elaborate court protocol, pomp and tremendous cultural production in all fields, including architecture, silver, paintings, theatre, and literature.

Detail of one of the figures before treatment

Detail of one of the figures after treatment

This panel presents three straight rows of eight three-quarter length figures, organised according to age and rank and divided by balustrades. Their features are idealised and represent generic types: the mature princes are bearded, while the younger ones are clean shaven with side locks of hair. Their arms are crossed in a gesture of submission and allegiance and their gaze is directed towards their father and ruler at the centre. The princes are dressed in elaborate court ceremonial attire and either crowned or turbaned according to their rank. The clothing is richly detailed and exquisitely rendered with the precision of manuscript illustration. The alternating brilliantly coloured robes, rich detailing in gold paint of the brocades, shawl fabrics, fur collars, and most of all armlets, epaulettes, crowns, daggers and swords worn by the princes and princelings, impart an air of luxury and wealth to the scene, skilfully evoking the splendours of the imperial treasury. The painting acts as a historical record of the dynasty, giving specific information regarding the status of the princes and their role in the court and line of succession.

For more information about the painting’s history and its historical context, do have a read of the Lot Essay for this picture on Christie’s website where there is an informative essay written by Dr. Layla S. Diba.

Detail of one of the figures before treatment

Detail of one of the figures after treatment

In the 1920s, this painting was bought by the American artist and collector Frederic Clay Bartlett (1873-1953), to be hung in his studio at the family’s winter retreat “Bonnet House” in Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

The painting was offered for sale at Christie’s London in April 2021. Simon Gillespie was asked by Christie’s to inspect the picture in order to put forward an initial condition report and treatment proposal that could be shared with the buyer of the painting. After the sale, Simon Gillespie Studio worked closely with both Christie’s and the new owner of the painting, a major museum in Asia, to bring the picture back to looking its best: the picture is magnificent, but it was clear that it would need extensive treatment in order to resolve some of the clumsy interventions it had undergone over the years.

The painting is on canvas, made up of three individual horizontal pieces of canvas stitched together. On inspection prior to treatment, the canvas joins were visible on the front of the painting as a result of being pushed forward during a previous lining treatment. The original canvas had been lined in the past with a heavier, more open-weave canvas. This lining was of poor quality and little regard has been given to the surface appearance of the painting. The heavy use of adhesive (probably BEVA) gave the painting a stiff, board-like character. There were a number of pronounced and visually disturbing folds, creases and other deformations in the original canvas which were not resolved in the previous lining but rather were ironed into the work, and in places this past treatment had caused the folded and compressed original canvas to break and the paint layers to crack along the creases. As a result there are many paint losses and abrasions associated with these creases and folds. There were a number of areas across the painting where original canvas had been lost. During the last lining, canvas inserts had been added to these losses. These had been made from different pieces of cloth with a variety of weave structures. One particularly large insert was in the face of one of the figures on the bottom row where the original had been entirely lost. The canvas was stretched onto a wooden strainer which was weak, not particularly well constructed and not solid enough to provide adequate support for the painting: it flexed during handling.

Detail showing joins in canvases, raking light, before treatment

Detail showing cracks and paint losses along folds, seen in normal light, before treatment

The composition was painted in oil paint over a red-coloured ground layer; there were also details applied in gold paint.

It was quite obvious that the whole painting had been heavily overpainted, covering much of the original paint layers. There was evidence of more than one historical overpainting campaign. In some areas such as the background between the figures, old fills were visible and this filling material had been smeared over the original composition and then retouching had been applied on top. The background was extensively overpainted, though the original paint was visible in the areas of the inscriptions. The layers of overpaint were very thick in places and had been applied crudely. The overpaint was particularly thick and heavily applied along the bottom edge of the painting, extending quite significantly up into the bottom quarter of the work; this might be an indication that the painting suffered particular damage along the bottom which is typical of works exposed to damp, for example by being stored poorly with contact to the ground. The retouching generally was discoloured, crude and mismatched and had a flattening effect on the three-dimensionality of the composition.

Initial tests showed that underneath the overpaint, the original paint was in a condition to be expected of pictures of this type and period: in areas, the paint layers were in poor condition and had suffered considerable abrasion and delamination. There was a crack network present throughout much of the paint layers and many of these cracks had raised edges and associated paint losses.

The painting also had layers of discoloured top coats/varnishes and dirt which were darkening the painting and obscuring the image. The surface had an overall dull and very patchy gloss level. It is likely that the painting was cleaned and revarnished in the past, and thick areas of dark varnish-like remnants could be seen in some of the interstices, for example in the areas of the pearls. In this particular case the remnants showed a grey discolouration, indicating at least a layer of synthetic material, which tends to attract dust to the surface due to static. UV images of the surface also showed the uneven application of the old varnishes on the surface, as well as previous retouching campaigns. Some thicker areas of varnish fluoresced more strongly in UV light, making it difficult to assess the overpaint and original paint underneath.

There was a layer of dirt present over the surface of the whole painting.

Detail of bottom section of painting showing extent of overpaint, seen in ultraviolet light

Detail showing overpaint in the background around one of the inscriptions

Detail showing discoloured retouching on hand

Detail showing overpaint ironed into canvas fold

Having studied the painting closely and carried out testing to understand the layers of varnish and overpaint and of original paint, a condition report and treatment proposal were written up and presented to representatives of the museum which had acquired the painting.

The team at the start of work, documenting and discussing the painting

Once the treatment proposal was approved, treatment began in earnest.

Testing was carried out alongside observation in UV light to understand the stratigraphy of the paint, overpaint and varnish layers, and to ascertain the safest and most appropriate method for removing the overpaint and varnish layers one by one. Tests were performed using a wide range of materials, from free solvents to gels and emulsions, including water-based methods. This process clarified the previously supposed layer structure of the surface coatings and varnishes. An uppermost synthetic (not analysed) layer was distinguished, and a layer of the most recent overpaint directly underneath this layer. A very tough, presumably vinyl-containing (not analysed) layer was found underneath these upper two layers, and underneath this the oldest overpaint, which was highly insoluble and discoloured. Further testing showed that the red ground layer was extremely sensitive to water-based formulas and certain solvents, as were the red colours in the costumes and the gold. It was at this point that the cleaning of the gold had to be reconsidered due to its sensitivity; in some areas it was decided that despite the old overpaint being visually disturbing, reducing its appearance at the retouching stage would be safer for the paint layers than attempting to remove all of it.

Cleaning was carried out in stages, using methods most appropriate to each layer that needed to be removed. Firstly was the removal the uppermost layer of varnish which was a thick, clear layer which had not discoloured significantly. During removal of this layer the most recent layer of overpaint was of a similar solubility and was also removed. Secondly, the second layer of varnish was removed. After that, the team addressed the overpaint. The removal of the overpaint layers which were present underneath the top two layers of varnish and the most recent overpaint presented a challenge because of the sensitivity of the red ground layer. In some areas, the previous lining process had ironed thick, insoluble overpaint into areas of damaged original paint, making it almost impossible to safely separate. This was also true of areas of putty or fill which had been covered by overpaint, and appeared to be oil based and almost completely insoluble. A combination of several suitable methods was found, although some of the overpaint was not possible to remove due to the fragility of the original paint and ground.

Detail showing first varnish layer and overpaint partially removed, normal light, during treatment

Detail showing area after cleaning with some remains of overpaint

After the cleaning process, the next step was to address the structure of the painting. The old lining and patches were removed, and the old patches retained as a historical record. The creases and fold marks were gently flattened where possible. The canvas was relined onto a medium grained Belgian artist’s linen, using BEVA gel. Where there were previously old canvas patches, these were replaced with patches made from a canvas of a similar weave to the original canvas, and primed using alkyd primer. The canvas was then stretched onto a new custom-made stretcher.

The painting during structural treatment of the canvas

The canvas after lining before being stretched onto its new stretcher

The painting after lining

The painting was then given a brush varnish to act as an isolating layer between the original paint and the materials we would be using to reintegrate the losses in the composition.

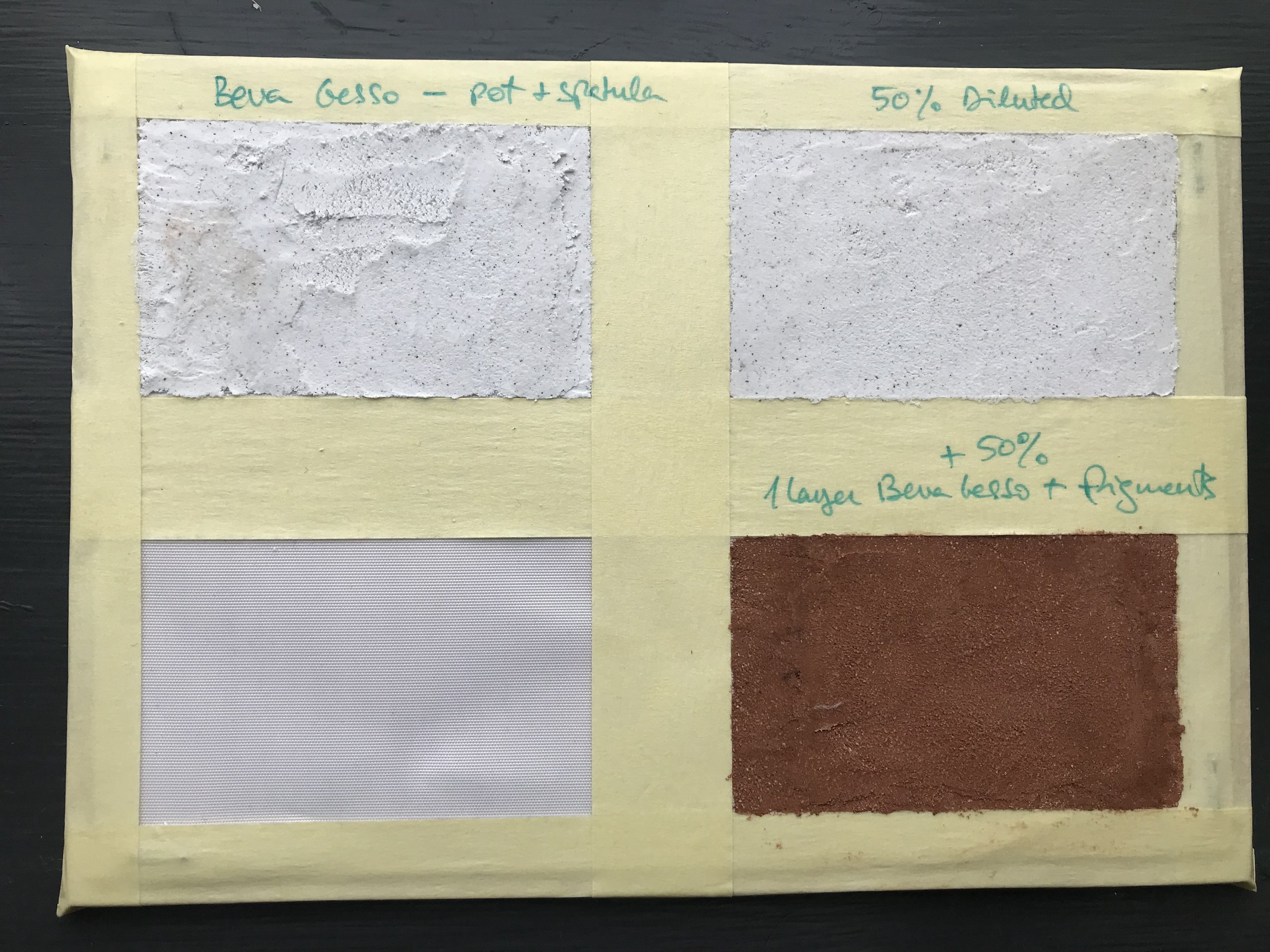

Firstly, the losses needed to be filled. It was necessary to choose a filling material that would be flexible enough to allow the painting to be safely rolled during treatment and transport, and therefore our team made several mock-ups on test pieces of canvas to find the most suitable fill adhesive. The fill was then textured to match the texture of the original canvas.

Some of the filling tests carried out on sample pieces of canvas

Testing and recording the results

After that, retouching began. Overall, retouching on the painting was kept as minimal as possible, and care was taken not to cover the original paint and to confine work to areas of loss. In the area of the gold passages where it had not been possible to remove some earlier overpaint a different approach was taken as some of these old overpaints were discoloured and visually disturbing. In these areas where it was felt necessary the discoloured overpaint was toned in order to reduce the impact. Much of the abraded areas were left without retouching where appropriate, to maintain the painting’s aged appearance and reflect the painting’s history. After discussions with the client and relevant experts, it was decided that the inscriptions should be left for future scholars to interpret, rather than completing with retouching. For reconstructing the lost face, an image of a complete face from elsewhere in the painting was projected onto the surface in order to retouch it.

Before treatment

During varnish and overpaint removal

After lining

Applying texture to the fill in the area of the lost face

During filling

The face after retouching

Detail of one of the figures before treatment

Detail of one of the figures before treatment

Detail of one of the figures before treatment

Detail of one of the figures before treatment

Detail of one of the figures before treatment

Detail of one of the figures before treatment

Detail of one of the figures before treatment

Detail of one of the figures after treatment

Detail of one of the figures after treatment

Detail of one of the figures after treatment

Detail of one of the figures after treatment

Detail of one of the figures after treatment

Detail of one of the figures after treatment

Detail of one of the figures after treatment

It was an immensely rewarding project and we were delighted by the response of our several contacts at the institution that had acquired the painting, who variously wrote “Many thanks to you and your team for doing a great restoration job on the Qajar painting” and “Please convey my appreciation to all your team for the conservation work done for the painting. “ and “Now I know definitively, once more, why your studio deserves its very good reputation.”